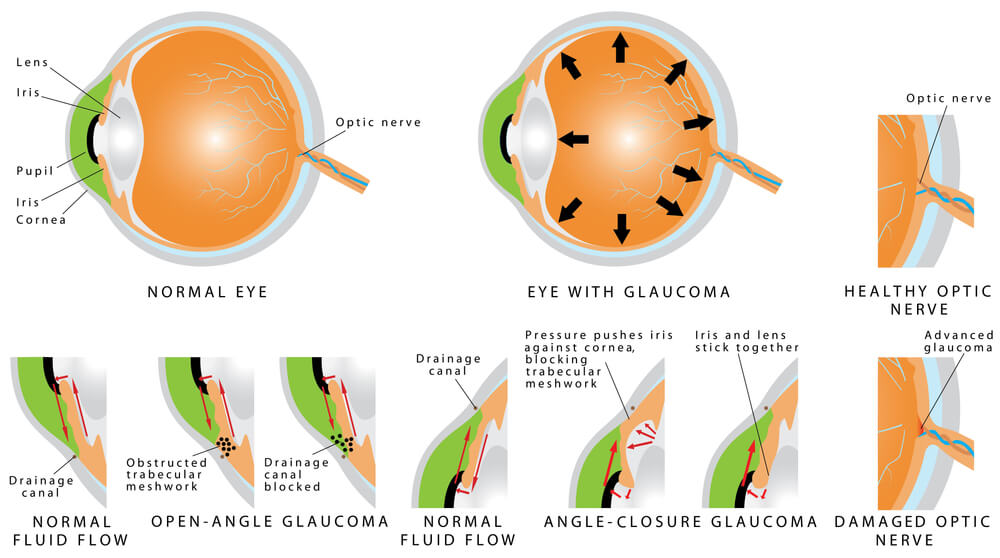

Glaucoma is defined as a characteristic change in the optic nerve that is associated with loss of peripheral vision. Typically, glaucoma is also associated with high eye pressure. Glaucoma is a group of diseases of which there are a multitude of causes. Traditionally, glaucomas have been classified on the appearance of the drainage system within the eye. The drainage system, which is called the trabecular meshwork, is a circular mesh-like drain that is the anterior chamber “angle” of the eye. The angle itself, is located at the circular border where the white part of the eye (the sclera) meets the clear part of the eye (the cornea). When the drainage system is blocked or impeded, a buildup of fluid occurs in the eye, which in turn results in increased eye pressure or intraocular pressure (IOP).

We will discuss the more common types of glaucoma below.

Types of Glaucoma

- Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

- Normal Tension Glaucoma (Low Tension Glaucoma)

- Traditional Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (elevated eye pressure)

- Secondary Open Angle Glaucoma

- Pseudoexfoliation Glaucoma

- Pigmentary Glaucoma

- Steroid Induced Glaucoma (Medication Induced Glaucoma)

- Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

- Chronic Angle Closure Glaucoma

- Secondary Angle Closure Glaucoma

- Neovascular Glaucoma

- Inflammatory Glaucoma

- Glaucoma Suspect (Borderline Glaucoma)

- Childhood Glaucoma (Congenital Glaucoma)

- Narrow Angle & Plateau Iris Syndrome (Glaucoma risk factors)

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

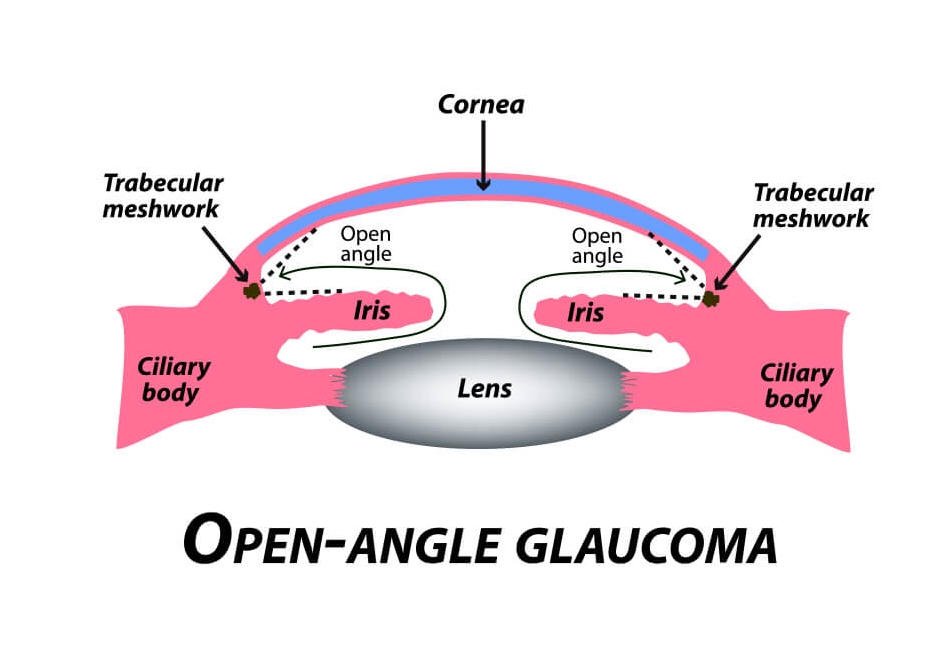

The most frequently encountered glaucoma is Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG), also known as chronic open angle glaucoma or (COAG). It is characterized by an elevated eye pressure (IOP), changes in the optic nerve which include cupping and atrophy, and visual field defects. By definition, in “primary” glaucomas there are no inherent eye abnormalities or systemic disease causing the glaucoma. Upon examination of the drainage system via a special technique called gonioscopy, a normal appearing drainage system and anterior chamber angle is seen. There are no noted abnormalities visible.

Both eyes tend to be involved at the same time and to a similar degree. The prevalence of POAG in the United States is about 2%, with approximately 3 million Americans being affected. Worldwide, it is the second leading cause of blindness. As there are no early symptoms, approximately 50% of people with glaucoma don’t know that they have the disease. In fact, most cases are detected after age 40.

Although the exact cause of POAG is not known, there are a number of known risk factors which include: high eye pressure, advanced age, racial background (African and Hispanic ancestry), thin corneal thickness and a positive family history. Both males and females are affected by POAG equally.

Normal Tension Glaucoma (Low Tension Glaucoma)

Normal Tension Glaucoma (NTG), otherwise known as low tension glaucoma (LTG), is very similar to POAG. The big key difference is the absence of an elevated pressure. Although there is no universally accepted “normal” pressure value, generally speaking, an eye pressure reading in the 20 mmHg range is considered normal. Eyes with NTG do not have an intraocular eye pressure elevated in this range.

Treatment for patients with NTG is the same as for all types of glaucoma, the intraocular pressure is lowered. Even the eye pressure in NTG is not elevated by the traditional definition, studies have shown that further decreasing the eye pressure does lower the risk of optic nerve damage and peripheral vison loss.

Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma

Similar to primary open angle glaucoma, patients with secondary open angle glaucoma have a drainage system which can be freely visualized. There is no obvious obstruction of the drainage structures in the anterior chamber angle. There is, however, an increase in the resistance to outflow of fluid from the eye that results from ocular or systemic causes. This buildup of fluid results in increased eye pressure.

While the drainage system may be freely visible, careful examination of the eye with a microscope and special examination lens called a gonio lens, subtle clues can be seen that may reveal the cause of the glaucoma. We will review examples of secondary open-angle glaucoma which include pseudoexfoliation, pigment dispersion and medication induced glaucoma.

Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome/Glaucoma

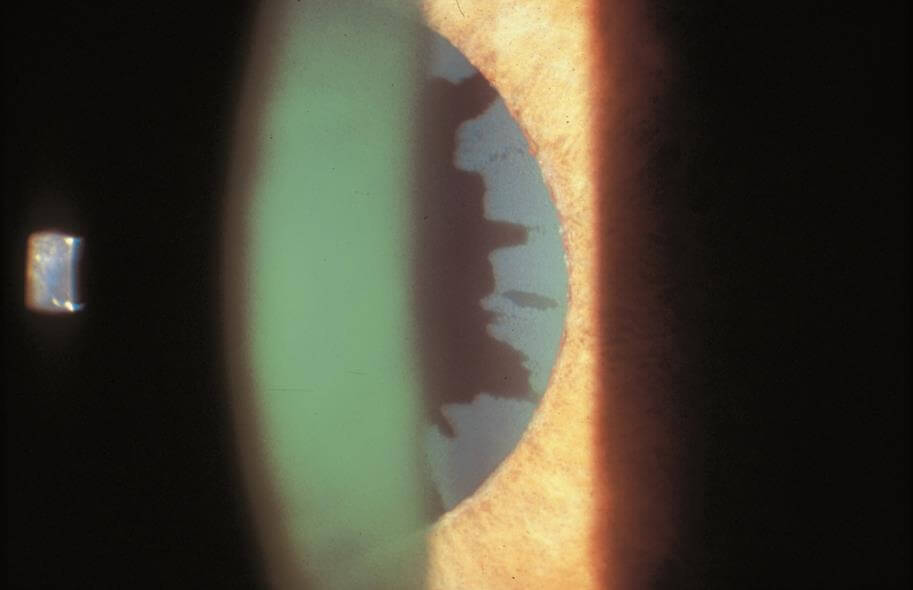

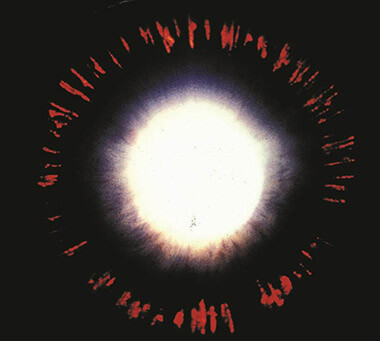

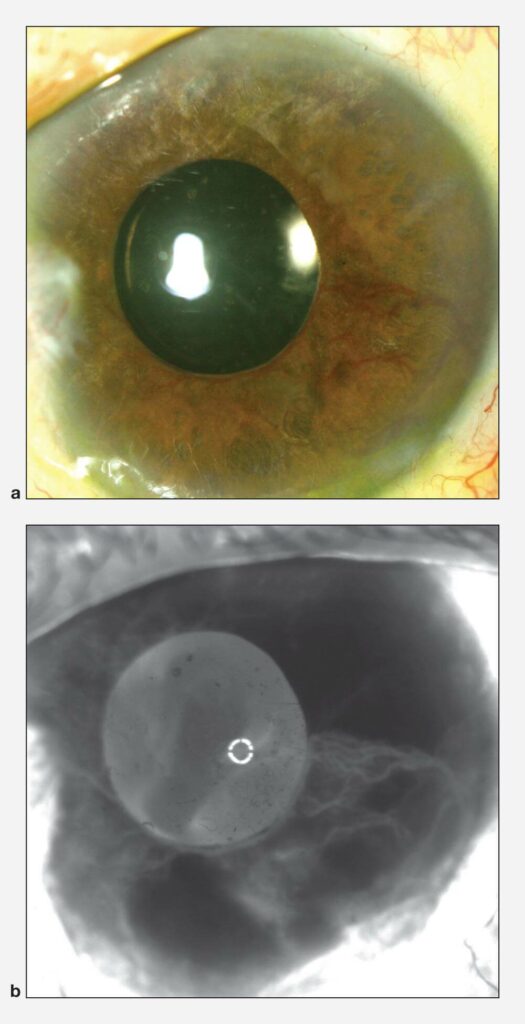

Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome may result in a specific type of open angle glaucoma characterized by the deposition of “dandruff-like”, fluffy, protein material on the structures within the eye. Characteristic deposits can be seen on the iris (specifically the pupillary border), the lens capsule, zonules (support system for the lens) and drainage system. This disease can be found in one or both eyes but commonly it is asymmetric on presentation. Risk factors traditionally included age, (mostly seen in patients above 70 years of age), female gender and Scandinavian decent. Not all patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome progress to pseudoexfoliation glaucoma.

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

The protein material can build up in the in the trabecular meshwork or drain, causing an elevation in the intraocular pressure and resultant glaucoma. Similar to the other glaucomas, the treatment of pseudoexfoliation glaucoma is lowering of the eye pressure using a combination of medicines, lasers and surgery.

Pseudoexfoliation has associated findings which include weak zonules (weakened lens support) resulting in lens instability (phacodenesis), floppy iris (iridodonesis), poor pupillary dilation, and iris atrophy. These characteristics can make cataract surgery much more complex. Lens dislocation can occur during surgery and eye pressure spikes can occur immediately after the surgery. The eye surgeons of Michigan Glaucoma & Cataract have specialized training and experience in dealing with pseudoexfoliation patients, prior to, during and immediately after cataract surgery.

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

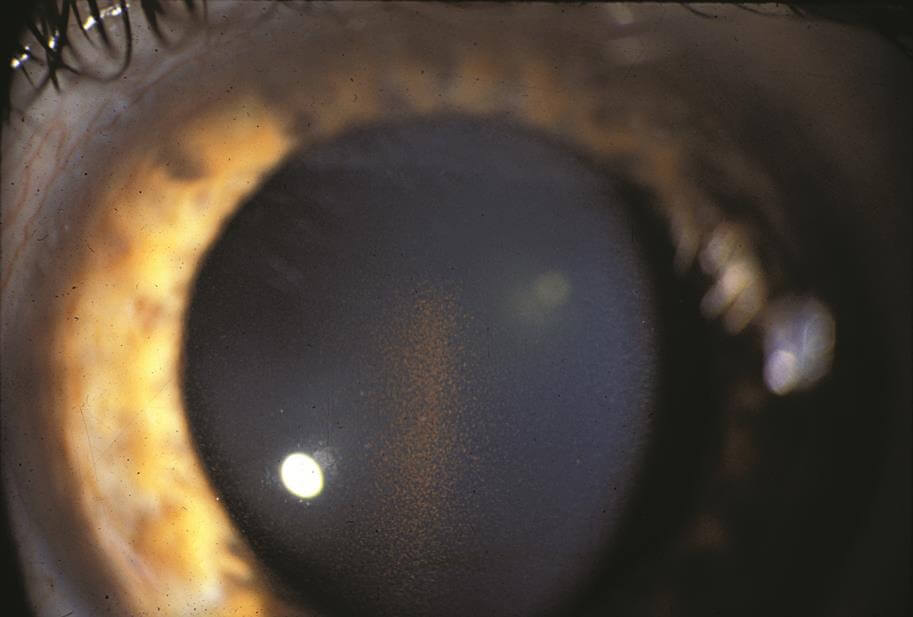

Pigment Dispersion Syndrome

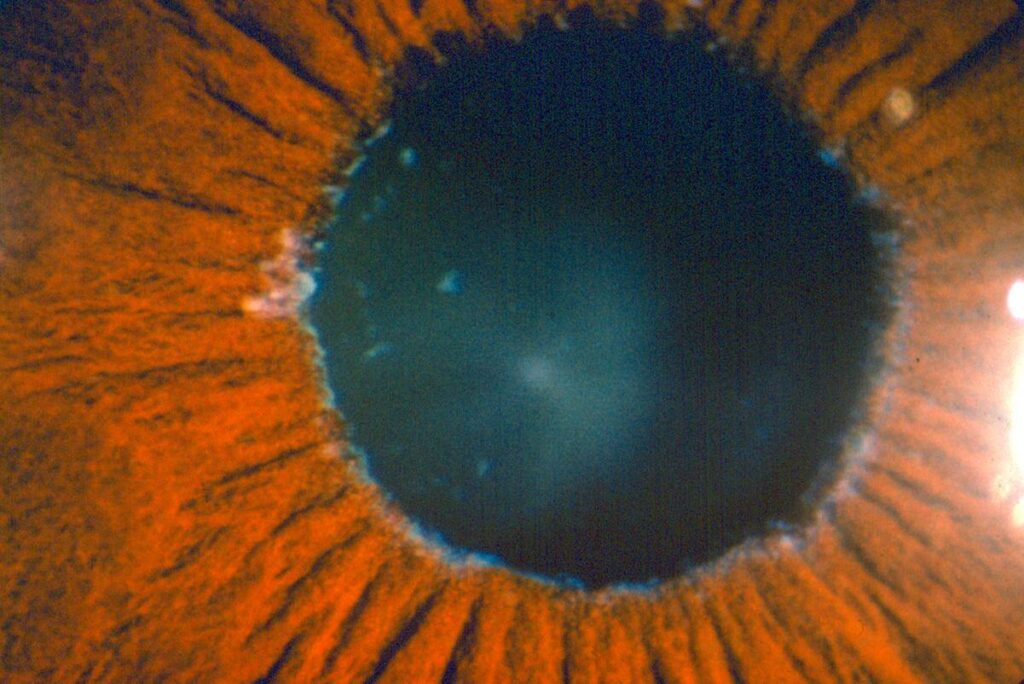

Pigment dispersion is thought to occur as a result pigment granules being released or sloughed off the iris or colored portion of the eye. The loss of pigment from the iris, results in classic and characteristic, mid-peripheral transillumination defects which are seen on examination. Other findings include pigment deposits on the cornea (Krukenberg spindle) the trabecular meshwork and lens capsule (Scheie stripe). Risk factors for pigment dispersion syndrome include Caucasian race, male gender, near-sightedness, (myopia) and younger age. Typically, it is diagnosed earlier in life, between the ages of 20 to 50. It should be noted that, not all patient with pigment dispersion develops pigmentary glaucoma.

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

The mechanism which results in increased eye pressure is the deposition of the pigment granules in the trabecular meshwork drainage system. The clogged trabecular meshwork can be visualized with gonioscopy, a specialized viewing technique. The trabecular meshwork is easily recognizable as it is stained a dark brown with liberated pigment granules. The outflow of fluid produced in the eye (aqueous fluid) is impeded which in turn increases the eye pressure. The syndrome is often characterized by wide fluctuations in the IOP which is thought to be due to an increase in the amount of pigment being liberated.

As with other types of glaucoma, the treatment for pigmentary glaucoma is the lowering of the intraocular pressure using a combination of medicines, lasers and if needed surgery. Patients with pigment dispersion respond particularly well to laser treatments. (Laser Trabeculoplasty).

Steroid (Medication) Induced Glaucoma

A number of medications have been associated with increasing the pressure of the eye, most notably corticosteroids “steroids”. Although steroids used in treating the eye, such as eye drops, eye injections used to treatment edema and inflammation, are most likely to cause an elevated eye pressure, any form of steroid can increase the eye pressure. Prescription strength oral, topical creams and injections can also cause increase in eye pressure. Even over-the-counter medications such as steroid creams and nasal sprays have been implicated in elevating the eye pressure.

It is estimated that ~30% of all people have a mild-moderate elevation (up to 11 mmHg rise from baseline) with use of ocular steroids (drops or injectable) and 5% have an elevation of greater than 15 mmHg usually requiring treatment. Among patients with preexisting glaucoma, the likelihood of a pressure elevation rises significantly.

More recently, it has been observed that patients receiving various multiple non-steroid intravitreal injections (e.g. bevacizumab/Avastin®, ranibizumab/Lucentis®, aflibercept/Eylea®) can also have sustained intraocular pressure rise. These medications are often used for retinal disease including macular degeneration, diabetes, and macular edema (swelling).

Treatment for steroid (medication) induced glaucoma is similar to other secondary open-angle glaucomas and medications are usually successful. Cases requiring surgical intervention also have a high degree of success.

Other examples of secondary open-angle glaucoma include:

- Inflammatory (uveitic) Glaucoma

- Intraocular Tumor-Induced Glaucoma, where the tumor blocks the drainage system

- Lens Induced (cataract associated) Glaucoma (e.g. phacolytic, lens particle, phacoantigenic)

- Traumatic Glaucoma (e.g. accidental trauma/hit to the eye)

- Elevated Episcleral Venous Pressure, (e.g. Sturge-Weber Syndrome, arteriovenous fistula, thyroid-associated orbitopathy) This occurs because there is an increase in back pressure that fluid of eye drains into. These causes are typically outside of the eye itself.

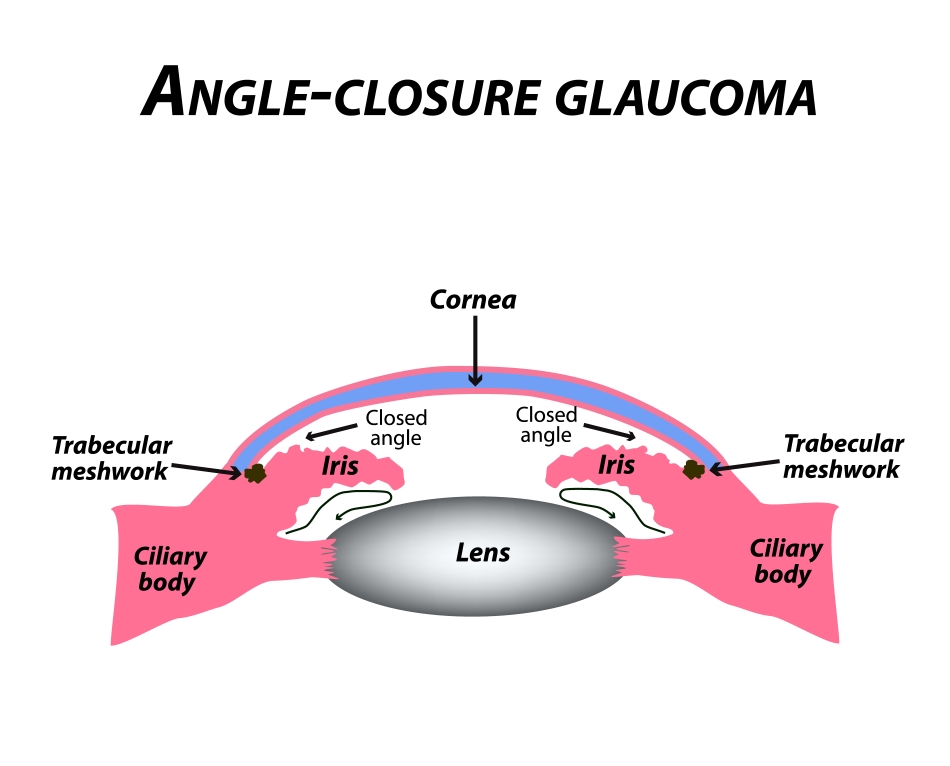

Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Acute angle-closure glaucoma occurs when there is a sudden and dramatic increase in the eye pressure. It is true eye emergency and if not properly diagnosed and treated, progressive and permanent ocular damage can occur in the eye in a matter of hours to days. The patient typically presents with a sudden onset of pain, redness of the eye and blurred vision. The pain is typically a headache that is centered above the brow of the affected eye. Nausea, vomiting, and extreme sweating are commonly seen and may lead to improper diagnosis and treatment in the emergency room setting.

Examination of the eye shows a very crowded space inside the eye which impedes the outflow of fluid from the eye resulting in a build up and high eye pressure. Gonioscopy shows a shallow anterior chamber which effectively allows the iris to block the trabecular meshwork or drainage system from functioning. It should be noted that the iris bows forward, impeding the drainage system only after the pupil blocks the normal flow of the fluid in the eye.

Treatment of an acute angle closure attack is aimed at “opening up the drain” to lower the eye pressure, thus breaking the attack. Treatment typically begins medically with both oral medications and topical eye drops. Pilocarpine, a drop that causes the pupil to constrict and pull on the iris, mechanically opening the drain has been shown to work. A laser hole (laser iridotomy) is usually needed to help create a “by-pass” channel for the fluid in the eye to drain, hence reducing the eye pressure, breaking the attack and preventing repeat attacks. The fellow, non-affected eye typically requires the same laser procedure as well to prevent a similar angle closure attack.

After an acute angle-closure attack, the vision is often affected and the visual recovery variable. Following an attack, the cornea can develop damage and become slightly cloudy, despite a normalized pressure. This occurs because the cells that make up the innermost layer of the cornea, become less viable and die off. This most often occurs in patients with pre-existing corneal degenerations such as Fuchs’ dystrophy, or in patients with long-standing angle-closure prior to treatment.

Other changes and signs that can be seen after an attack include a discolored iris. Because of high eye pressure, the iris tissues can die off due to ischemic necrosis or (lack of blood flow). The iris will then appear lighter in color with respect to the fellow eye. The pupil may also remain permanently dilated and unresponsive to light nor eye drops as the iris sphincter muscle is damaged. Due to the sudden rise in pressure, white spots can form on the front of the natural lens that is inside the eye. These white spots are called “glaukomflecken” and are a classic sign that an attack has occurred.

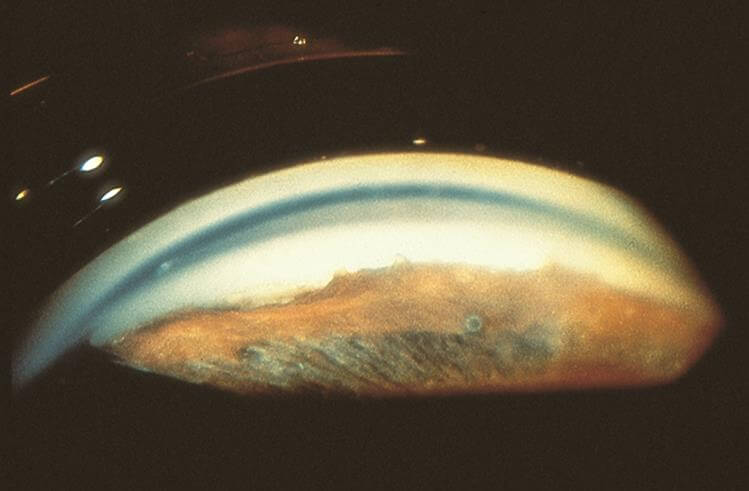

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma

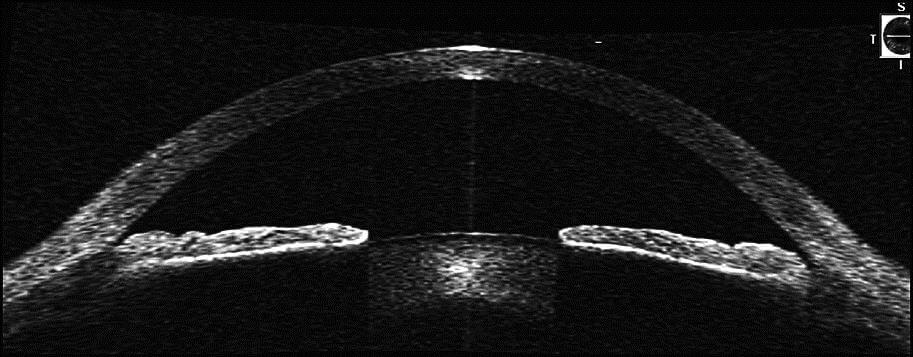

The primary angle-closure glaucomas are conditions which result from the obstruction of the drainage system by iris tissues, without an obvious systemic or ocular cause. In chronic angle-closure glaucoma (CACG), peripheral scar tissue called peripheral anterior synechiae or PAS, bridge the anterior chamber and effectively dam the drainage system, preventing outflow of eye fluid. The eye fluid builds up and the intraocular pressure rises.

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

Angle-closure glaucoma caused by the pupillary (iris) block can be divided in either acute (discussed above) or chronic angle closure. In both cases, the initiating event is contact between the front of the natural lens and the back of the iris. Because of the anatomy, the iris captures the eye fluid, which circulates from back to front, much like a sail catches wind. The iris bellows forward and closes off the drainage system. With repeated undetected attacks, permanent scar closure of the drainage system can occur. This is called synechial closure and it is a hallmark of chronic angle closure glaucoma.

Chronic angle-closure glaucoma is often overlooked as a diagnosis and may be mis-treated as primary open-angle glaucoma. Examination of the angle drainage structures with gonioscopy is crucial in recognition of subtle changes and proper classification. The ophthalmologists at MGS, with their fellowship training, are highly trained in detecting subtle changes of scar formation that may lead to chronic angle closure glaucoma.

As with other forms of glaucoma, the primary treatment for CACG is to lower the eye pressure. However, the pupillary block component of the disease needs to be treated with a laser iridotomy forming a bypass channel for the eye fluid to flow. The goal of a laser iridotomy is to slow or stop progressive, chronic peripheral scar (PAS) formation and angle dysfunction that leads to chronic angle closure. Even with a successful iridotomy, progressive angle closure may occur and as such repeated gonioscopy is done. Most patients will respond to laser and medical treatment but sometimes glaucoma surgery may be necessary.

Secondary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

As in primary angle-closure glaucoma, patient with secondary open angle glaucoma have anterior chamber angle/drainage system that is at least partly occluded. There is often peripheral scar formation which extends between the iris and the drainage system, (PAS or peripheral anterior synechiae). However, in secondary angle-closure, the narrowing of the anterior chamber angle is associated with an obvious cause, either systemic or ocular. Again, careful gonioscopic examination can reveal the cause of the closure, a skill that all MGS doctors have as a result of their glaucoma fellowship training.

Neovascular Glaucoma

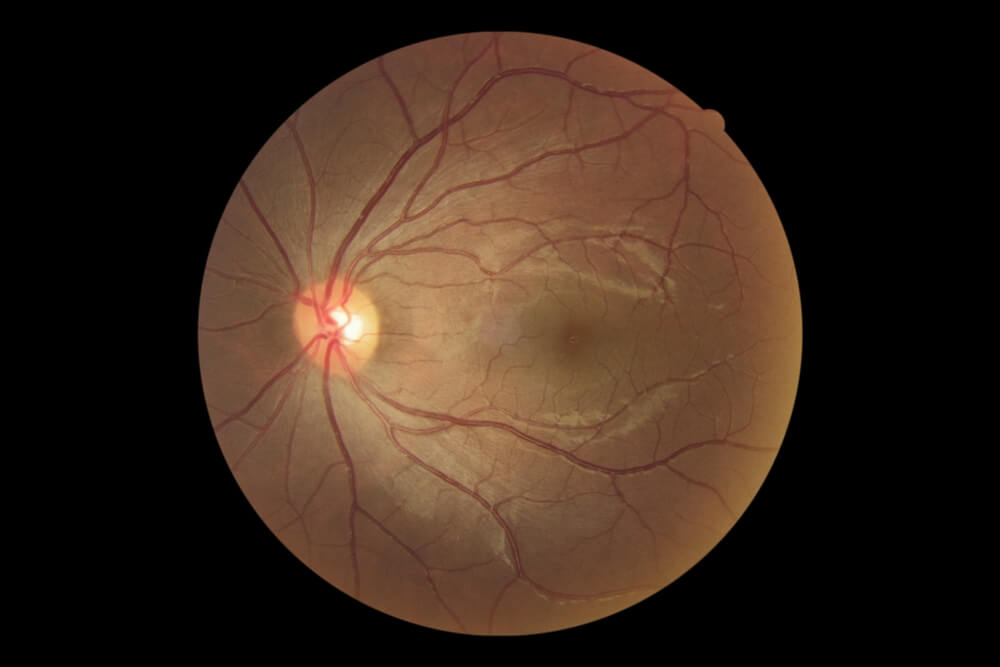

Neovascular glaucoma, a severe type of secondary angle-closure glaucoma, results from the formation of abnormal blood vessel growth in the iris and trabecular meshwork. This abnormal neovascularization (new blood vessel growth) is associated with bleeding and scarring within the eye, as well as PAS formation in the angle leading to secondary angle-closure glaucoma. The drainage system is blocked off and the eye pressure increases.

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

Like all forms of secondary glaucoma, neovascular glaucoma is the result of other ocular and/or systemic disease. The most common causes of neovascular glaucoma include uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, central retinal vein occlusions or “mini strokes in the eye”, and ocular ischemic syndrome which can result from carotid artery disease. Other less common causes included chronic inflammation inside the eye, trauma, tumors, radiation treatments and other diseases affecting blood vessels (both in the eye and systemically).

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

Patients with neovascular glaucoma often present with acute (sudden) vision changes, pain, eye redness, and high intraocular pressure. Treatment consists of controlling the intraocular pressure and treating the underlying disease. A glaucoma drainage implant is often placed surgically as often medications do not work in controlling the eye pressure.

One should note that blood vessels are present in the normal anterior chamber angle. Often they can be seen upon routine gonioscopy. The visibility of the angle blood vessels depends on the color of the iris and the width of the angle. Visible blood vessels can be seen upon gonioscopic examination in more than 50% of blue-eyed individuals, but less than 10% of brown-eyed humans. They are more commonly noted in wide than narrow angles. MGS doctors perform gonioscopy on all patients and are experts at distinguishing normal versus abnormal angle blood vessels.

Inflammatory Glaucoma

Ocular inflammation, or uveitis can lead to a variety of problems, including elevated intraocular pressure, glaucoma, corneal disease, cataracts, and retinal disease, as well as scarring in the conjunctiva, cornea, iris, anterior chamber angle, and retina.

Inflammatory glaucoma results from a variety of mechanisms, with formation of PAS and posterior synechiae (scar tissue between the iris and the lens) ultimately leading to elevated intraocular pressure. Additionally, there can be internal damage to the drainage system, that can cause the intraocular pressure to increase.

As with other forms of secondary glaucoma, the most important treatment aims at the underlying cause, often with topical and/or oral steroids and other anti-inflammatory medications. Severe inflammatory glaucoma that is associated with systemic disease such as rheumatological disease is typically managed by a team of specialist. The physicians of MGS work with uveitis (inflammatory) eye specialists and rheumatologist to optimize care. Treatment of elevated intraocular pressure is initially done with glaucoma medications, though surgical treatment is often necessary due to the aggressive nature of inflammatory glaucoma.

Glaucoma Suspect (Borderline Glaucoma)

Patients who may show some signs of glaucoma or may have risk factors for developing glaucoma but do not have definitive disease are called glaucoma suspects. Patients can be classified as “low risk” or “high risk” glaucoma suspects depending on the number of risk factors present. Classically, patients that have one of the following risks factors are glaucoma suspects:

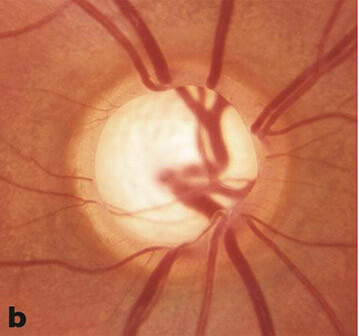

- Optic nerve or nerve fiber layer changes suspicious of glaucoma

- Intraocular pressure of greater than 21 mmHg

- Visual field changes consistent with glaucoma

© 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology

Several criteria have been associated with an increased risk of glaucoma. Patients may also be considered if they have some of the following:

- Level of intraocular pressure rise/fluctuations in eye pressure

- Cup-to-disc ratio (optic nerve appearance)

- Family history of glaucoma

- Age

- Race

- Central corneal thickness

- Associated diseases (e.g. diabetes, myopia)

Glaucoma suspects are routinely followed with testing and examination, as there is no way to predict which suspects will go on to develop glaucoma. Your MGS physician will discuss your risks factors with you and determine a regular follow-up schedule that actively monitors your status.

Narrow Angle and Plateau Iris Syndrome

While both a narrow angle and plateau iris can be associated with development of angle closure glaucoma, they do not necessarily result in glaucoma. Instead, both are anatomic descriptions of the anterior chamber angle between the cornea and iris.

Narrow Angle

Patients with a narrow anterior chamber angle are at risk for developing both acute and chronic angle-closure glaucoma. Studies have attempted to predict which patients will go on to develop glaucoma, but none have been consistently validated. Not all patients with narrow angles necessarily need treatment. However, those with intraocular pressure elevation, peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS), appositional angles, history of previous angle closure, positive family history, and/or symptoms of intermittent angle closure should be treated with a laser iridotomy. Regardless of a whether a patient is treated or not, all those with a narrow angle should be warned of the signs/symptoms of an angle closure attack or intermittent angle closure, including: eye pain, eye redness, blurry vision, multi-colored halos, headache, nausea, and vomiting.

There are several systemic medications that are associated with an increased risk of acute angle-closure attack. These medications include over-the-counter cold and allergy medications, urologic medications, and certain anti-depressants. Please let your ophthalmologist know if you take any of these types of medications with any regularity, as their use may influence your doctor’s decision to treat you.

Plateau Iris Syndrome

In plateau iris syndrome, the iris has a unique and characteristic anatomic appearance. The iris is flat centrally and the anterior chamber (anterior portion of the eye) is of normal depth centrally, but on gonioscopy the angle is narrow. Often plateau iris is confused with a narrow angle secondary to a pupillary block mechanism, as described above. Younger patient with near-sightedness undergoing an acute angle closure attack should be closely evaluated for Plateau Iris.

Although the mechanism of plateau iris is different than that of a narrow angle with pupillary block angle closure, the initial treatment with a laser iridotomy is the same; some anterior chamber angle widening may be noted, but patients with a plateau iris will have a persistent narrow angle despite patent iridotomy (hole in the iris). These patients are often discovered when an angle-closure attack occurs in the presence of a patent iridotomy. The mechanism appears to be an anatomic abnormality of both the peripheral iris and ciliary body which is anteriorly rotated in such a fashion that it pushes a dilated pupil to occlude the drainage system. Additional treatment for patients with plateau iris may include close observation, miotic medications, laser iridoplasty, or lens/cataract extraction.

With proper examination techniques and specialized testing, your MGS doctor can detect and determine if you have plateau iris syndrome.

Childhood Glaucoma (Congenital Glaucoma)

Childhood glaucomas encompass both primary congenital glaucoma (also called pediatric or infantile glaucoma which are diagnosed shortly after a baby is born) as well as juvenile glaucoma which may be diagnosed after age 3 and into early adulthood.

Please refer to Childhood (Congenital) Glaucoma.